Module 1: Chapter 2 — Expressions

Expressions in C

Expressions are the fundamental building blocks of any C program. They combine data and operators to perform computations and produce results.

Key Points About Expressions:

- Formed from atomic elements: variables, constants, or function return values.

-

Operators act on data to produce results (e.g.,

+, -, *, /, %). -

Expressions can be simple (like

a + b) or complex (like(x * y) + func(z)). - C expressions are more flexible and powerful compared to older languages such as FORTRAN or BASIC.

The Basic Data Types

C89 defines five fundamental data types that form the foundation of the language:

- char → stores a single character (1 byte).

- int → stores integer values (size varies by platform).

- float → stores floating-point numbers with ~6 digits precision.

- double → stores double-precision floating-point numbers (~10 digits).

- void → represents no value, used for functions that return nothing or for generic pointers.

Important Notes:

- The

chartype usually represents ASCII values. -

Size of

intdepends on system architecture:- 16-bit systems → int = 16 bits

- 32-bit systems → int = 32 bits

- Always write portable code without assuming fixed size.

-

Floating-point values follow the IEEE representation. The range is

at least

1E-37 to 1E+37.

Modifying the Basic Types

C allows type modifiers to adjust the meaning of base data types for precision, size, or sign handling.

Available Modifiers:

- signed → allows both positive and negative values.

- unsigned → stores only non-negative values, doubles the positive range.

- short → reduces storage size (commonly 16-bit).

- long → increases storage size (commonly 32-bit or 64-bit).

Key Notes About Modifiers:

-

int can be modified with

signed,unsigned,short,long. -

char can be

signedorunsigned. -

double can be modified by

long(i.e.,long double). -

In C99 →

long longandunsigned long longwere added. - By default,

intis signed.

Data Type Sizes and Ranges

The following table summarizes the minimal ranges and typical sizes for all C data types:

| Type | Typical Bits | Minimal Range |

|---|---|---|

| char | 8 | -127 to 127 |

| unsigned char | 8 | 0 to 255 |

| int | 16 / 32 | -32,767 to 32,767 |

| unsigned int | 16 / 32 | 0 to 65,535 |

| long int | 32 | -2,147,483,647 to 2,147,483,647 |

| long long int (C99) | 64 | -(263 - 1) to 263 - 1 |

| unsigned long long int (C99) | 64 | 0 to 264 - 1 |

| float | 32 | 1E-37 to 1E+37 (~6 digits precision) |

| double | 64 | 1E-37 to 1E+37 (~10 digits precision) |

| long double | 80 | 1E-37 to 1E+37 (~10 digits precision, extended range) |

Signed vs. Unsigned Integers

-

The high-order bit (MSB) determines the sign in

signed integers:

- 0 → Positive

- 1 → Negative

- Negative numbers use two's complement representation.

- Unsigned integers double the positive range but cannot represent negative numbers.

-

Example:

0111111111111111= +32,767 (signed int)

1111111111111111= -1 (signed int)

1111111111111111= 65,535 (unsigned int)

Type Specifier Shortcuts

When a modifier is used without a base type, int is

assumed.

signed→ same assigned intunsigned→ same asunsigned intlong→ same aslong intshort→ same asshort int

Identifiers and Variables in C

Identifiers

- Definition: Identifiers are names given to variables, functions, labels, and other user-defined elements.

-

Rules:

- Must begin with a letter (a-z, A-Z) or an underscore (_).

- Subsequent characters may include letters, digits (0-9), or underscores.

-

Cannot include special symbols like

!,@, or spaces. -

Identifiers are case-sensitive, so

count,Count, andCOUNTare all distinct. -

Keywords such as

int,while,forcannot be used as identifiers.

-

Correct Examples:

count,test23,high_balance -

Incorrect Examples:

1count,hi!there,high...balance -

Significance of Length:

- In C89: first 6 characters of external identifiers and 31 of internal identifiers are significant.

- In C99: external identifiers → 31, internal identifiers → 63 significant characters.

- In C++: at least the first 1024 characters are significant.

- External Identifiers: Used in external linking (e.g., function names, global variables shared across files).

- Internal Identifiers: Not linked externally, e.g., local variables inside a function.

Variables

A variable is a named memory location that stores a value which may change during program execution. Every variable must be declared before use.

Examples of Variable Declarations:

int i, j, l;

short int si;

unsigned int ui;

double balance, profit, loss;

-

Declaration Syntax:

type variable_list; - Type Independence: Variable names are independent of their type; the compiler determines type by declaration.

Where Variables Are Declared

- Inside Functions: Local variables

- As Function Parameters: Formal parameters

- Outside All Functions: Global variables

Local Variables

- Declared within a block or function.

- Exist only while their block is executing (created at entry, destroyed at exit).

- Cannot be accessed outside their declaring block.

-

Default storage: stack, unless declared with

static. - Declared variables in inner blocks can hide variables in outer blocks with the same name.

Example: Variable Shadowing

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int x = 10;

if (x == 10) {

// hides the outer x

int x = 99;

printf("Inner x: %d\n", x);

}

printf("Outer x: %d\n", x);

return 0;

}

Output: Inner x: 99 and

Outer x: 10

In C89, local variables must be declared at the start of a block. In C99 and C++, variables can be declared at any point before first use.

Formal Parameters

- Variables declared inside the parentheses of a function definition.

- Behave like local variables, destroyed after function execution ends.

- Receive argument values during a function call.

Example:

int is_in(char *s, char c) {

while (*s)

if (*s == c) return 1;

else s++;

return 0;

}

Global Variables

- Declared outside of all functions.

- Accessible across the entire file (file scope).

- Stored in a fixed memory region, persisting throughout program execution.

- Can be shadowed by local variables of the same name.

- Best practice: minimize usage to avoid unintended side effects.

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

int count; // global

void func1(void) {

int temp = count;

printf("func1 temp: %d\n", temp);

}

void func2(void) {

int count; // local

for (count = 1; count < 5; count++)

putchar('.');

}

int main(void) {

count = 100;

func1();

func2();

printf("Global count: %d\n", count);

return 0;

}

The Four Scopes in C

| Scope | Meaning |

|---|---|

| File Scope | Identifiers declared outside all functions; visible throughout the file. (Global variables) |

| Block Scope | Identifiers declared inside a block (between { and }). Includes function parameters. |

| Function Prototype Scope | Applies to identifiers declared in function prototypes; visibility limited to the prototype itself. |

| Function Scope |

Applies only to labels (targets of goto) inside a

function.

|

Type Qualifiers in C

const

-

Definition: The

constqualifier specifies that a variable’s value cannot be changed by the program after initialization. -

Syntax Example:

const int a = 10;- declares an integer that cannot be modified. -

Usage in Functions:

constcan protect function arguments from modification, particularly when using pointers:#include <stdio.h>

void sp_to_dash(const char *str);

int main(void) {

sp_to_dash("this is a test");

return 0;

}

void sp_to_dash(const char *str) {

while(*str) {

if(*str==' ') printf("-");

else printf("%c", *str);

str++;

}

} -

Standard Library: Many functions like

strlen(const char *str)useconstto ensure the argument string is not modified. - Benefits: Protects against unintended modification and allows compiler optimizations.

volatile

-

Definition: The

volatilequalifier tells the compiler that a variable’s value may change unexpectedly, outside program control. - Usage: Common in hardware access, global variables modified by interrupts, or memory-mapped I/O.

-

Example:

volatile int timer_flag; -

Combination with const:

const volatile char *port = (const volatile char*)0x30;- read-only for the program but may change externally.

Storage Class Specifiers in C

extern

- Definition: Declares a variable or function that is defined elsewhere with external linkage.

- Purpose: Allows referencing global variables or functions across multiple files without redefining storage.

-

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

extern int first, last;

printf("%d %d", first, last);

return 0;

}

int first = 10, last = 20; -

Best Practice: Place

externdeclarations in header files included in multiple source files.

static

- Definition: Creates variables with permanent storage that are limited in scope to their function or file.

-

Local Static Variables:

- Declared inside a function.

- Maintain value between function calls.

- Not accessible outside their function.

- Example:

int series(void) {

static int series_num = 100;

series_num += 23;

return series_num;

} -

Global Static Variables:

- Declared outside any function.

- Visible only within the file (internal linkage).

- Cannot be accessed from other files, preventing unintended side effects.

- Example:

static int series_num;

void series_start(int seed) {

series_num = seed;

}

int series(void) {

series_num += 23;

return series_num;

} - Benefits: Allows encapsulation of variables within a function or file, reducing conflicts and enhancing modularity.

Variable Initialization

In C, variables can be assigned an initial value at the time of declaration. Initialization allows assigning a known starting value, preventing the use of garbage data.

General Form

type variable_name = constant;

Examples

char ch = 'a';

int first = 0;

double balance = 123.23;

Important Points

- Global and static local variables are initialized only once, at program startup.

- Local variables are initialized each time their block is entered.

- Uninitialized local variables contain unpredictable (garbage) values.

- Uninitialized global and static local variables are automatically initialized to zero.

Constants

Constants are fixed values that do not change during program execution. They are also called literals and can belong to any data type.

Types of Constants

-

1. Integer Constants:

- Whole numbers without fractional parts

-

Can be positive or negative (e.g.,

10,-45)

-

2. Floating-Point Constants:

- Contain decimal points or use scientific notation

- Examples:

12.34,4.56e-2

-

3. Character Constants:

- Enclosed in single quotes — represent a single character

-

Examples:

'A','5','%' - Wide-character constants use

Lprefix -

Example:

wchar_t wc;

wc = L'A'; // wide-character constant

-

4. String Constants:

- Sequence of characters enclosed in double quotes

- Example:

"Hello World"

-

5. Enumeration Constants:

- Named integer constants defined using

enum -

Example:

enum Weekday { SUN, MON, TUE, WED };

- Named integer constants defined using

Type Suffixes

Uoru→ Unsigned integer-

Lorl→ Long integer or Long double Forf→ Float constantLLorll→ Long long integer (C99)

Examples:

int a = 123; // Integer constant

long int b = 35000L; // Long integer

unsigned int c = 100U; // Unsigned integer

float f = 12.34F; // Float constant

double d = 123.45; // Double constant

long double ld = 1001.2L; // Long double constant

💡 Quick Tip: Use suffixes like L,

U, or F to explicitly define constant

types and prevent type conversion errors.

Hexadecimal and Octal Constants

What Are They?

- In C, numbers can be represented in different number systems — not just decimal (base 10).

-

Octal constants use base 8 (digits

0-7). -

Hexadecimal constants use base 16 (digits

0-9and lettersA-Fora-f). - These constants help programmers work directly with binary and memory-level data.

Where Are They Used?

- In embedded systems and hardware programming (e.g., memory addresses, registers).

-

When working with colors in graphics (

0xFF0000→ red color in RGB). -

To represent bit patterns or flags efficiently

(

0x01,0xFF). - In system-level code for permissions, masks, or device control.

Syntax Rules

-

Octal constants: Start with

0(zero). -

Hexadecimal constants: Start with

0xor0X. - They represent integer values and can be assigned to any integer-type variable.

Examples:

int dec = 10; // Decimal 10

int oct = 012; // Octal 12 → Decimal 10

int hex = 0xA; // Hexadecimal A → Decimal 10

int hex2 = 0x80; // Hexadecimal 80 → Decimal 128

int color = 0xFF0000; // Hex code for red color

Quick Comparison

| Format | Prefix | Base | Digits Used | Example | Decimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decimal | — | 10 | 0-9 | 10 |

10 |

| Octal | 0 |

8 | 0-7 | 012 |

10 |

| Hexadecimal | 0x or 0X |

16 | 0-9, A-F | 0xA |

10 |

💡 Easy Trick to Remember: 0 → Octal,

0x → heXadecimal. The prefix tells the compiler which

base you are using!

String Constants

A string constant is a sequence of characters enclosed in double quotes.

"This is a test"

-

Strings differ from characters —

'a'is a single character, while"a"is a string of length 1. -

C has no formal

stringtype; strings are arrays of characters.

Backslash Character Constants (Escape Sequences)

C supports special backslash character constants, also called escape sequences, for non-printing or special characters.

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

\b |

Backspace |

\f |

Form feed |

\n |

New line |

\r |

Carriage return |

\t |

Horizontal tab |

\" |

Double quote |

\' |

Single quote |

\\ |

Backslash |

\v |

Vertical tab |

\a |

Alert (beep) |

\? |

Question mark |

\N |

Octal constant |

\xN |

Hexadecimal constant |

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("\n\tThis is a test.");

return 0;

}

Output: Prints a new line, a tab space, and then “This is a test.”

Operators in C

C is a powerful and expressive language, rich in built-in operators that enable concise and efficient programming. Operators form the core of most C expressions and play a more central role in C than in many other programming languages. Broadly, C operators are classified into the following categories:

- Arithmetic Operators

- Relational Operators

- Logical Operators

- Bitwise Operators

- Special Operators (e.g., assignment, sizeof, conditional)

The Assignment Operator

In C, the assignment operator (=) can be used within

expressions — a feature that distinguishes C from many older languages

like BASIC, Pascal, or FORTRAN. The general form is:

variable_name = expression;

The left-hand side (lvalue) must be a variable or memory location that can store data, and the right-hand side (rvalue) is any valid expression whose value is assigned to that variable.

- lvalue: Refers to an object that can appear on the left side of an assignment (modifiable memory).

- rvalue: Represents the data value that can appear on the right side of an assignment.

Example:

int x = 10;

int y;

y = x + 5; // y is assigned the value 15

Type Conversion in Assignments

When variables of different data types are mixed in an expression, C automatically converts one type to another, following specific conversion rules. In an assignment, the expression on the right-hand side is converted to the type of the variable on the left-hand side before the assignment takes place.

int x;

char ch;

float f;

ch = x; // int → char

x = f; // float → int

f = ch; // char → float

f = x; // int → float

- When assigning int → char, only the lower 8 bits of the integer are stored.

- When assigning float → int, the fractional part is truncated.

- When assigning char → float, the character’s ASCII value is converted into float format.

- Precision Loss: Converting from a larger to a smaller data type may cause information loss.

Outcome of Common Type Conversions

| Target Type | Expression Type | Possible Information Loss |

|---|---|---|

| char | int (16 bits) | High-order 8 bits lost |

| char | int (32 bits) | High-order 24 bits lost |

| short int | int (32 bits) | High-order 16 bits lost |

| int (32 bits) | long int | None |

| int | float | Fractional part lost |

| float | double | Rounding due to precision limits |

Multiple and Compound Assignments

-

Multiple Assignment: Several variables can be

assigned the same value in one statement.

x = y = z = 0; -

Compound Assignment: Combines arithmetic with

assignment for compactness.

x = x + 10; // same as

x += 10;Similar shorthand operators exist for subtraction (

-=), multiplication (*=), division (/=), and modulus (%=).

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators perform basic mathematical calculations. The

modulus operator (%) works only with integers. Division

between integers truncates the fractional part.

| Operator | Action |

|---|---|

| + | Addition |

| - | Subtraction |

| * | Multiplication |

| / | Division |

| % | Modulus (remainder of division) |

| ++ | Increment by 1 |

| -- | Decrement by 1 |

Example:

int x = 5, y = 2;

printf("%d ", x / y); // Output: 2

printf("%d", x % y); // Output: 1

Increment and Decrement Operators

The increment (++) and decrement (--)

operators simplify repetitive addition or subtraction by one. They can

be used as prefix or

postfix operators:

int x = 10, y;

y = ++x; // Prefix: increments before use

y = x++; // Postfix: increments after use

Prefix and postfix increments differ in the timing of the operation relative to the expression evaluation.

Relational and Logical Operators

Relational operators compare two values, while logical operators combine or invert logical conditions. In C, any nonzero value is considered true, and zero is false.

Relational Operators

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

| > | Greater than |

| >= | Greater than or equal |

| < | Less than |

| <= | Less than or equal |

| == | Equal to |

| != | Not equal to |

Logical Operators

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

| && | AND |

| || | OR |

| ! | NOT |

Example:

if (x > 5 && !(y < 3) || z < = 10)

printf("Condition is true");

Example: Implementing Logical XOR

#include <stdio.h>

int xor(int a, int b) {

return (a || b) && !(a && b);

}

int main(void) {

printf("%d", xor(1, 0)); // Output: 1

printf("%d", xor(1, 1)); // Output: 0

printf("%d", xor(0, 1)); // Output: 1

printf("%d", xor(0, 0)); // Output: 0

return 0;

}

Operator Precedence

Operators are evaluated in a specific order of precedence. Parentheses can override this order to clarify or control the evaluation sequence.

| Category | Operators (Highest → Lowest) |

|---|---|

| Increment / Decrement | ++ -- |

| Unary Operators | - (unary minus) |

| Arithmetic | * / % + - |

| Relational | > < >= <= |

| Equality | == != |

| Logical | ! && || |

| Assignment | = += -= *= /= %= |

Increment and Decrement Operators

What Are They?

-

The increment operator

++adds 1 to its operand. -

The decrement operator

--subtracts 1 from its operand. - These are unary operators, meaning they operate on a single operand.

-

Commonly used to simplify expressions such as

x = x + 1;orx = x - 1;.

Examples:

int x = 5;

++x; // same as x = x + 1 → x becomes 6

--x; // same as x = x - 1 → x becomes 5

Prefix vs Postfix

-

The prefix form (

++xor--x) increments/decrements the variable before its value is used in an expression. -

The postfix form (

x++orx--) increments/decrements the variable after its value is used.

Example:

int x = 10;

int y = ++x; // prefix → x becomes 11, y = 11

x = 10;

y = x++; // postfix → y = 10, then x becomes 11

Efficiency

Most compilers generate faster and more optimized code using

++ and -- compared to

x = x + 1 or x = x - 1. They are ideal for

loops, counters, and pointer arithmetic.

Operator Precedence (Arithmetic)

| Precedence | Operators |

|---|---|

| Highest | ++, -- (prefix) |

- (unary minus) |

|

*, /, % |

|

| Lowest | +, - |

💡 Use parentheses to override precedence, e.g.

(x + y) * z.

Relational and Logical Operators

What Are They?

- Relational operators compare two values to determine their relationship.

- Logical operators connect or invert relational expressions.

-

Both types of operators produce Boolean results —

either

1 (true)or0 (false). -

In C, any nonzero value is treated as

true, and zero isfalse.

Relational Operators

| Operator | Meaning | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

> |

Greater than | 5 > 3 |

True (1) |

>= |

Greater than or equal to | 3 >= 3 |

True (1) |

< |

Less than | 2 < 3 |

True (1) |

<= |

Less than or equal to | 4 <= 2 |

False (0) |

== |

Equal to | 5 == 5 |

True (1) |

!= |

Not equal to | 4 != 5 |

True (1) |

Logical Operators

| Operator | Meaning | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

&& |

AND | (5 > 3) && (2 < 4) |

True (1) |

|| |

OR | (5 < 3) || (2 < 4) |

True (1) |

! |

NOT | !(5 == 3) |

True (1) |

Truth Table for Logical Operators

| p | q | p && q | p || q | !p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Example Program:

#include <stdio.h>

int xor(int a, int b) {

return (a || b) && !(a && b); // XOR logic

}

int main(void) {

printf("%d", xor(1, 0)); // 1

printf("%d", xor(1, 1)); // 0

printf("%d", xor(0, 1)); // 1

printf("%d", xor(0, 0)); // 0

return 0;

}

Precedence (Highest to Lowest)

| Precedence | Operators |

|---|---|

| Highest | ! |

>, >=, <,

<=

|

|

==, != |

|

&& |

|

| Lowest | || |

💡 Use parentheses to group logical conditions. For example,

!(0 && 0) || 0 evaluates to true.

Bitwise Operators

What Are They?

- Bitwise operators perform operations on individual bits of integer values.

- They allow direct manipulation of binary data — a feature crucial in low-level programming.

- Commonly used in embedded systems, device drivers, encryption, and data compression.

Operators and Their Meanings

| Operator | Action |

|---|---|

& |

Bitwise AND |

| |

Bitwise OR |

^ |

Bitwise XOR (exclusive OR) |

~ |

One’s complement (NOT) |

>> |

Shift right |

<< |

Shift left |

Usage Example:

char ch = read_modem();

return (ch & 127); // clears parity bit (AND with 01111111)

Truth Table for XOR ( ^ )

| p | q | p ^ q |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Bit-Shift Operators

-

x << n: Shifts bits left by n positions (multiplies by 2ⁿ). -

x >> n: Shifts bits right by n positions (divides by 2ⁿ). - Bits shifted off are lost; zeros (or ones for negatives) are filled in.

Example:

unsigned char x = 7; // 00000111

x = x << 1; // 00001110 = 14

x = x << 3; // 01110000 = 112

x = x >> 2; // 00011100 = 28

| Operation | Effect |

|---|---|

| Left Shift (<<) | Multiplies by 2 for each shift |

| Right Shift (>>) | Divides by 2 for each shift |

Shift Operator Demo Program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

unsigned int i = 1;

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

i = i << 1;

printf("Left shift %d: %d\\n", j, i);

}

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

i = i >> 1;

printf("Right shift %d: %d\\n", j, i);

}

return 0;

}

One's Complement (NOT)

In C, the ~ operator flips every bit of a number. This is

called the bitwise NOT operation.

-

It turns all

1s into0s and all0s into1s. - If you apply it two times, you get the original value back.

Simple Example in C:

char encode(char ch) {

// Flip all bits of the character

return ~ch;

}

This function takes a character, flips all its bits, and returns the result.

💡 Bitwise operators like ~ only work with integer

types (like char, int, etc.).

They are very useful in areas like systems programming,

cryptography, and working directly with hardware.

Common C Operators and Their Uses

The ?: (Ternary) Operator

-

What it is: A shorthand for simple

if-elsestatements. -

Syntax:

condition ? expression_if_true : expression_if_false; -

How it works:

- If

conditionis true, the first expression runs.

- If false, the second expression runs. -

Example:

int x = 10;

int y = (x > 9) ? 100 : 200;

printf("%d", y); // Output: 100 -

Equivalent to:

if (x > 9) y = 100;

else y = 200;

The & and * (Pointer) Operators

- What they are: Used to work with memory addresses.

-

&(Address-of): Returns the memory address of a variable.

Example:m = &count;→ stores the address ofcountinm. -

*(Dereference): Accesses the value stored at a given address.

Example:q = *m;→ stores the value at addressmintoq. -

Pointer declaration:

int *ptr;→ declaresptras a pointer to an integer. -

Example Program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int target, source;

int *m;

source = 10;

m = &source;

target = *m;

printf("%d", target); // Output: 10

return 0;

}

The sizeof Operator

- What it is: A compile-time operator that returns the size (in bytes) of a variable or type.

- Used for: Writing portable programs that adapt to system architecture.

-

Syntax:

sizeof(variable)orsizeof(type) -

Example:

double f;

printf("%lu ", sizeof(f)); // 8 bytes

printf("%lu", sizeof(int)); // 4 bytes -

Returns type:

size_t(an unsigned integer type).

The , (Comma) Operator

- What it is: Allows multiple expressions to be evaluated in one statement.

- How it works: All expressions are evaluated left to right, but only the last expression’s value is used.

-

Example:

int x, y;

x = (y = 3, y + 1);

printf("%d", x); // Output: 4

The . and -> (Structure Access) Operators

- What they are: Used to access members of structures and unions.

-

.(Dot): Used when accessing directly through a structure variable. -

->(Arrow): Used when accessing through a pointer to a structure. -

Example:

struct employee {

char name[80];

int age;

float wage;

} emp;

struct employee *p = &emp;

emp.wage = 123.23; // using . operator

p->wage = 123.23; // using -> operator

The [ ] and ( ) Operators

-

( ): Used to group expressions and control operation precedence. -

[ ]: Used for array indexing — accesses elements by position. -

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

char s[80];

int main(void) {

s[3] = 'X';

printf("%c", s[3]); // Output: X

return 0;

}

Operator Precedence Summary

Operators are evaluated in a specific order of priority. Parentheses

( ) can override default precedence.

| Highest | ( ), [ ], -> |

|---|---|

!, ~, ++, --,

sizeof

|

|

*, /, % |

|

+, - |

|

<<, >> |

|

<, <=, >,

>=

|

|

==, != |

|

&, ^, | |

|

&&, || |

|

?: (Ternary) |

|

Assignment (=, +=, *= ...)

|

|

| Lowest | , (Comma) |

Tip: Always use parentheses ( ) to

make expressions clear and avoid ambiguity when using multiple

operators together.

System Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

The System Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is a step-by-step process used to design, develop, test, and maintain high-quality software systems. It ensures that software is created in a structured, organized, and efficient way.

Why SDLC is Important:

- Provides a systematic approach to software development.

- Reduces the chances of project failure.

- Improves planning, documentation, and testing.

- Ensures that user requirements are clearly defined and met.

- Allows for better communication among teams and stakeholders.

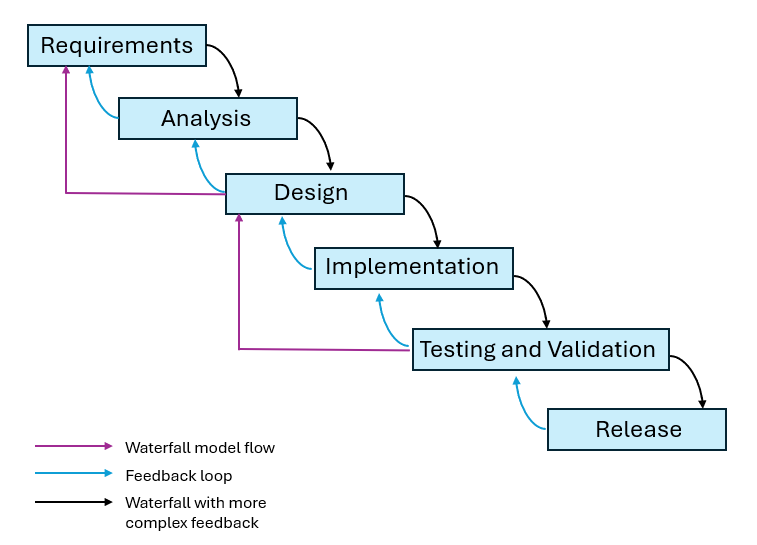

The Waterfall Model

One of the earliest and most popular SDLC models is the Waterfall Model. It follows a linear and sequential flow — meaning each phase must be completed before the next one begins.

(Waterfall Model Diagram)

Phases of the Waterfall Model:

-

1. System Requirements:

- Define what the system should do.

- Gather input from users and stakeholders.

- Output: A clear list of system goals and user requirements.

-

2. System Analysis:

- Analyze the system requirements in detail.

- Identify possible solutions and select the best one.

- Focus on “what” the system must achieve, not “how.”

-

3. System Design:

- Plan “how” the system will be built.

- Design data flow, architecture, user interfaces, and databases.

- Decide on hardware, software, and communication needs.

-

4. Coding (Implementation):

- Actual programs are written using a programming language (like C).

- Each module is coded, compiled, and tested individually.

- This is the phase explained in this book!

-

5. Testing:

- All modules are combined and tested as a complete system.

- Ensures the software works correctly and meets requirements.

- Defects and bugs are identified and corrected.

-

6. Deployment:

- The finished system is installed and delivered to the users.

- Training and documentation are provided for smooth usage.

-

7. Maintenance:

- Continuous support after deployment.

- Fix bugs, add updates, and improve performance over time.

- Keeps the system reliable and up to date.

Iteration in the Waterfall Model:

- Although it seems linear, phases often overlap in real life.

- Developers may need to go back to a previous phase if errors are found.

- This backflow is shown as “feedback arrows” in the waterfall diagram.

Important Note:

- If major issues are discovered late (during testing or coding), the project can fail.

- In large projects, this can mean millions of dollars and years of effort lost.

- That's why proper planning, analysis, and design are critical.